A key insight that emerged out of our regular informal brainstorming sessions at Tech Ceylon is that while Sri Lanka’s youth are heavy consumers of interactive digital content – social media, computer games, and the like – they have very little sense of how such content is created. This is particularly true for Tamil speaking youth in the Northern and the Eastern Provinces where computer literacy beyond passive consumption is nearly non-existent.

Moreover, Sri Lanka has a nascent IT industry that is facing a severe shortage of skilled human resource. According to top industry representatives, if the country is to raise its annual foreign income from IT-related products and services to USD 5 billion (from the current earnings of USD 1.2 billion) another 150,000 – 200,000 people should join the IT labour force in the next couple of years.

Idea

These realisations led to the conception of PyGame Boot Camp: an intensive one day programming camp for advanced level (high school) students. Using the popular PyGame game development library for the Python programming language language, the participants would code a fully functional 2D classical action game – similar to Nokia’s Snake, Space Impact, and Catch the Eggs. The camp would last between 6-8 hours and the participants would start from ground zero i.e. installing Python 3 and PyGame.

The inspiration for the boot camp came from a similar annual event organised by the Kyoto Micro-computing Society at the University of Kyoto aimed at computer science freshers with no prior programming experience.

The grand idea is inspiring as many youngsters as possible to consider a career in computer science and IT. To begin with we decided to target students in the mathematical science stream. That many of these students may naturally pursue careers in technology and engineering informed this choice.

Goals

The PyGame Boot Camp’s primary aim is getting the participants excited about the power of programming and what they can do with it. For most of the participants, the camp would give them their first taste of creating interactive digital content. Second, the camp would demystify the notion that such content creation is the preserve of a select (very bright) few and show that with the present day open source, free-to-use tools this is pretty straightforward. Third, the participants would get a thorough grounding in primary data structures and fundamental programming concepts such as conditional execution, iteration, and procedures. Finally, the camp graduates – having coded more than 150 lines and seen their code in action (quite literally) – would be confident of picking up further, more advanced, programming skills on their own. The camp would, in fact, explicitly point to resources that can help them improve.

Challenges

Certain conditions must be met for the camp to deliver on these goals.

A key constraint is the programming language of choice: the technicalities of the language should not burden the creative expression of the participants. It must be simple (dynamic), easy to understand, and not excessively clunky. We picked the Python language and the PyGame library because they broadly meet the criteria and Python has increasingly become the preferred programming language for a range of activities.

Moreover, the camp should sufficiently excite and inspire the participating students. In other words, the camp cannot be a bland introductory computer science class that starts by answering ‘what is a computer programme?’ It is also important that the participants are satisfied and fulfilled by the game they code. This means that the games developed during the day should have adequate functionality – such as scoring, screen transitions, and possibly sounds. Equally, the participants should avoid trying the extravagant – like coding a 3D game or even implementing gravity in a 2D setting – and failing.

Flyer for PyGame Boot Camp V 0.0

Trial run

On June 27, 2018, Tech Ceylon, along with the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, organised a trial run (zero-eth iteration) of the boot camp at the South Eastern University of Sri Lanka. The participants were first year engineering students, a few weeks into their first semester of study.

This is how we went about running the camp:

- Six mentors, all of them second year engineering students with a fair amount of programming experience, took a week to build a moderately complex game of their choice. They largely depended on online resources such as YouTube tutorials and the www.PyGame.org website for this purpose. We had four Sinhala speakers and two Tamil speakers as mentors.

- A notice was issued asking interested students to form linguistically monolithic groups of four and register. On a first-come-first-served basis, the first four Sinhala and the first two Tamil groups to register were picked for participation.

- On the day of the camp, each group was randomly assigned a mentor and coded the game their mentor had already built and knew well.

- Mentors’ task was not spoon feeding. They gave the larger picture about the game the group was about to build and let the participants fill in the details. A mentor typically did two things: (i) asked the right question whenever her group was stuck (for example, ‘what happens when you run needforspeed.exe? A game window pops up. Okay, so should opening up a game window be the first thing your code does?) (ii) helped with identifying the correct PyGame function for a particular task and fixed syntax errors.

- Participants mostly found solutions to their issues from the internet.

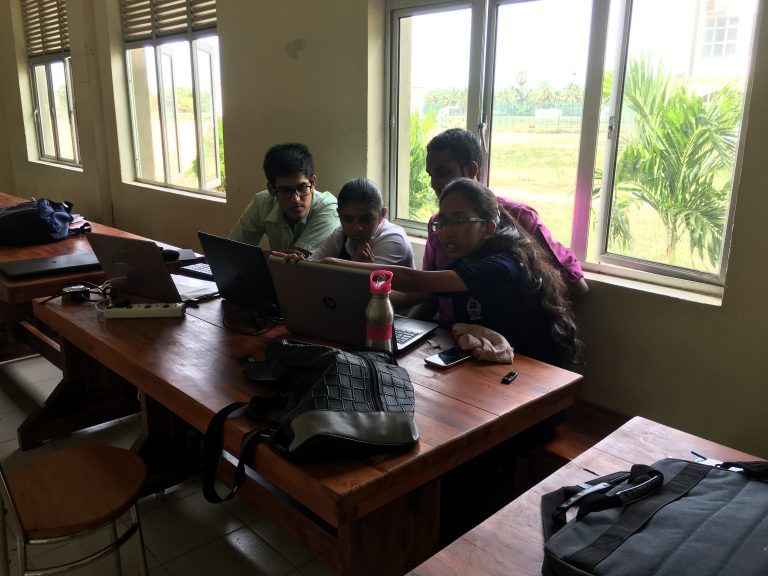

- At the end of the session, each group briefly introduced their game and let others play.

- We provided breakfast, snacks, and lunch for everyone.

Results

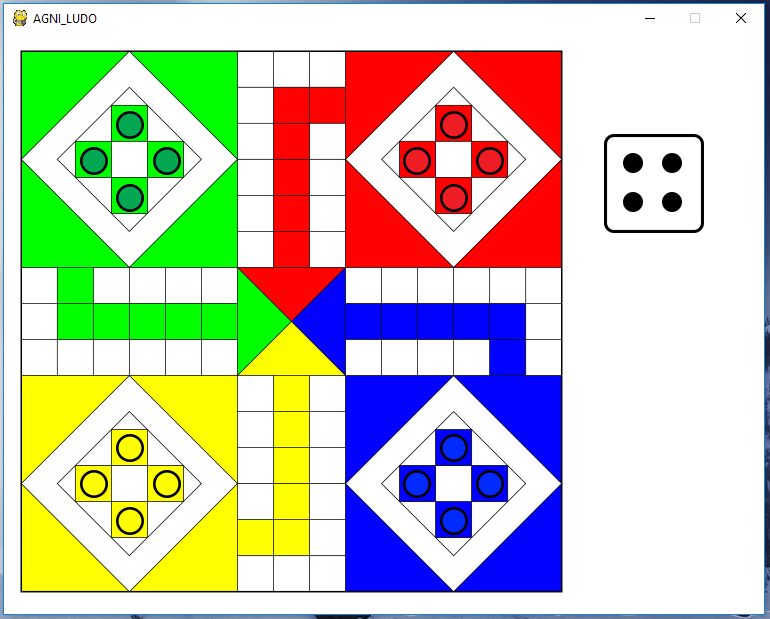

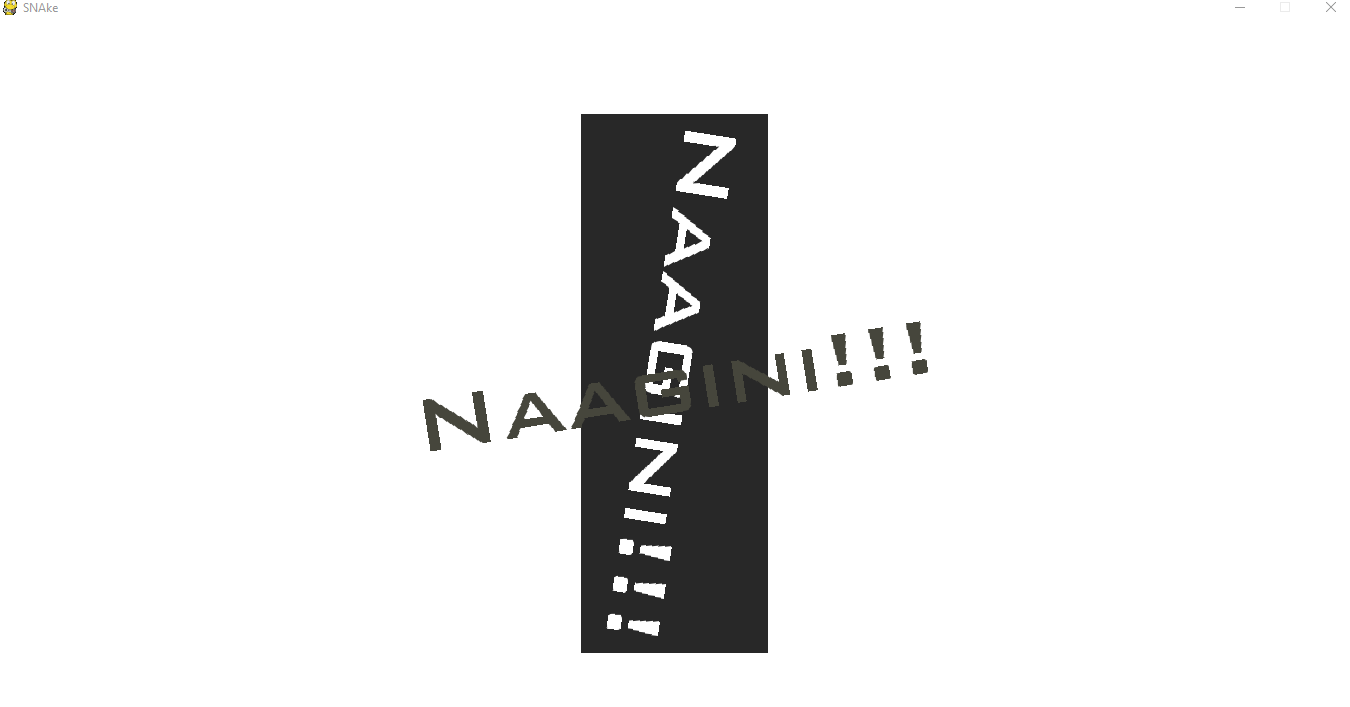

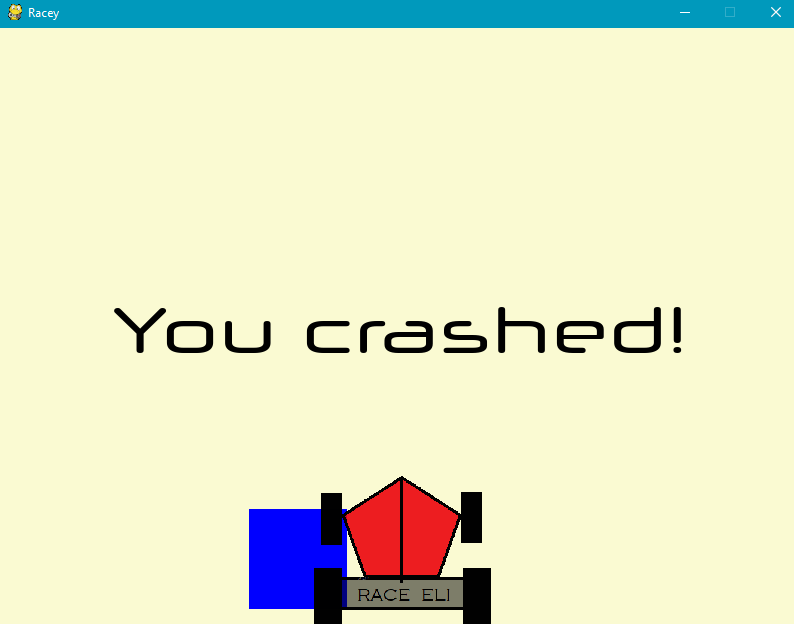

Out of the six, four groups fully completed their games. These were Snake, Catch the Apple, Avoid the Rock, and double-player Tic-Tac-Toe. The groups that failed to complete their games did so because of either attempting the complicated (ex multiplayer ludo) or the lack of preparation on the part of the mentor.

The group that completed Snake was awarded the prize for the most complete game whereas the bunch that tried ludo received a prize for the most valiant effort.

A sample of the games developed by the students

Reflections

The participants overwhelmingly stated that they had fun. Some contrasted the camp experience with their usual Python programming lab sessions – for example, writing a loop for printing useless ‘*’ patterns as against writing a loop to make an apple fall – and stated that the latter made far more intuitive sense. A fair number of students highlighted the fact the their course’s programming exercises involve writing a maximum of 20 lines of code and affirmed that writing over 150 lines for the game boosted their confidence in their own ability. The participants also found collaborative coding enriching. One student stated that he identified great online resources while searching for ways to fix a bug. The mentors who volunteered recorded their happiness in having shared their knowledge and enthusiastically pledged their support for future iterations of the boot camp.

While the original target audience of PyGame Boot Camp – namely, advanced level students – are unlikely to have had any programming experience, the participants in the trial run had a basic exposure to writing conditional statements, loops, and functions in Python. This is a subtle yet significant difference. As such the conclusions we draw from the trial run may not apply equally for complete beginners: for instance, there may be a need to creatively (and informally) introduce these basic computer science ideas right at the beginning of the session. All things considered, however, PyGame Boot Camp v 0.0 was a big success.

Tech Ceylon is currently planning v 1.1 which would bring together 30 advanced level students from Ampara and Batticaloa districts for a day of fun-filled coding and learning.

All smiles: students during the final demonstration